Featured Video

Judge Short Porch Homer 🔥

Baseball's Leading Hitter Is Defying the Trends of MLB Today

As he's not so much fearsome as immensely frustrating for opposing pitchers, the best hitter in Major League Baseball today is a guy who basically doesn't belong in today's baseball.

It's all there in his triple-slash ranks. This guy gets his hits and takes his walks, but he's not likely to slug anyone:

TOP NEWS

Cooking Up Paul Skenes Blockbuster Trade Packages amid Pirates Struggles

The Most Likely Player to Be Traded for Every MLB Team in 2025

Red Sox's Walker Buehler Shades Mets' Francisco Lindor For Rooting for His Ejection

It's OK if you looked at this and did a double take. Modern greats—think Juan Soto, Mike Trout and Vladimir Guerrero Jr.—don't hit like this. Heck, you have to go back to Tony Phillips in 1993 to find the last time a batter finished with an OBP over .440 and a SLG under .440.

Tony Gwynn never did it. Neither did Ichiro Suzuki, who's unsurprisingly a big fan of the guy who is doing it: Luis Arraez.

As far as how he's doing it, let's start by granting two things about the Minnesota Twins' multi-use infielder. Given that he was a .313 hitter with a .374 OBP between 2019 and 2021, this is not his first rodeo as a tough out. He also isn't devoid of power.

Arraez, 25, came into this season with a career high of four home runs, yet he has three through 58 games. And at 403 feet, the grand slam that he hit June 11 against the Tampa Bay Rays was the longest of his career.

But while he's clearly capable of doing so, trying to hit for power isn't Arraez's style. At 9.0 degrees and 22.2 percent, both his average launch angle and fly-ball rate are lower than ever in 2022.

In other words, Arraez wants no part of a "Fly Ball Revolution" that's very much ongoing in MLB. Since the dawn of the Statcast era in 2015, the league's launch angle and fly-ball percentage have gone up and stayed up as more and more hitters have chased the long ball.

The catch this year is that fly balls aren't traveling as far. That's not an accident, as a new model of ball and universal humidor usage have conspired to make the baseballs mushier than usual. The difficulty most hitters are having in adjusting is plainly visible in the league's collective batting average. At .241, it's the fourth-lowest in MLB history.

Though it's premature to call Arraez a trendsetter, his fellow hitters can learn something from him. For their convenience, let's break down his main lesson points.

Don't Give Away At-Bats

You've presumably heard of the three true outcomes (i.e., strikeouts, walks and home runs) and about how they may or may not be ruining baseball by making it more boring.

But given that two of those outcomes are indeed good results for hitters, dare we say that the real problem they're facing is a shortage of what we'll call competitive at-bats?

These would be at-bats free of non-competitive results, of which there are at least two. There are strikeouts, which have a zero percent chance of producing a hit. There are also pop-ups, which in 2022 have just a 2 percent chance of going for hits.

Since batted-ball data became available in 2002, this is the first season in which more than 22 percent of plate appearances end in strikeouts and more than 10 percent of all fly balls in play are pop-ups on the infield. Strip away the strikeouts and pop-ups, and only 72 percent of at-bats have been competitive in 2022. That's down from a peak of 79 percent in 2005.

Among individual hitters, however, you can take a wild guess who's not part of the problem in 2022 by way of a large percentage of competitive at-bats:

- 1. Luis Arraez, MIN: 89.8 percent

- 2. Jose Iglesias, COL: 88.8 percent

- 3. Steven Kwan, CLE: 87.8 percent

- 4. Michael Brantley, HOU: 86.8 percent

- 5. Jose Ramirez, CLE: 85.8 percent

This mostly has to do with how Arraez's swing is geared for contact. He's extraordinarily direct to the ball, resulting in the league's second-highest contact rate (91.9 percent) and third-lowest strikeout rate (8.5 percent).

As for infield pop-ups, Arraez has a lone "1" in that column this season. Between that and his 20 strikeouts, he's given away only 21 of his 235 at-bats.

That alone has meant a high hit probability for his other 214 at-bats, though other reasons help boost his batting average all the way up to .361.

Line Drives Are Good, but Ground Balls Can Be Too

Hitters have fallen in love with fly balls in recent years for a reason. That's where power is, as even in 2022 the .523 ISO (isolated power, or slugging percentage minus batting average) on fly balls is more than twice as high as the .239 ISO on line drives.

If it's merely hits that a hitter is after, though, line drives are the way to go. They have a .627 average in 2022, compared to .261 for fly balls.

Go figure who loves to hit line drives.

"I just only try to be hitting line drives. That's how I [contribute]," Arraez said earlier this month, according to Phil Miller of the Star Tribune. "I know Ichiro could hit home runs, but I just want to hit line drives."

And hit line drives he does. At 27.6 percent, Arraez's line-drive rate is four percentage points higher than the league average. He even gets more out of his line drives than the average hitter, batting .804 on them.

To be fair, this is where Arraez might be due for regression as the season goes along. At 91.4 mph, he hits his line drives more than 2 mph slower than the league average. Because hard-hit line drives have a better chance of becoming hits than softer-hit ones, it's no surprise that his .635 expected average on line drives is slightly lower than the league norm of .639.

Yet even if Arraez doesn't get as many line drives to find pay dirt between now and the end of the season, he should still collect plenty of hits like the first one in this clip:

That was a ground ball that left his bat at 94.7 mph and easily snuck through into left field for a single. Basically, the kind of hit we might as well start calling a "Luis Arraez Special."

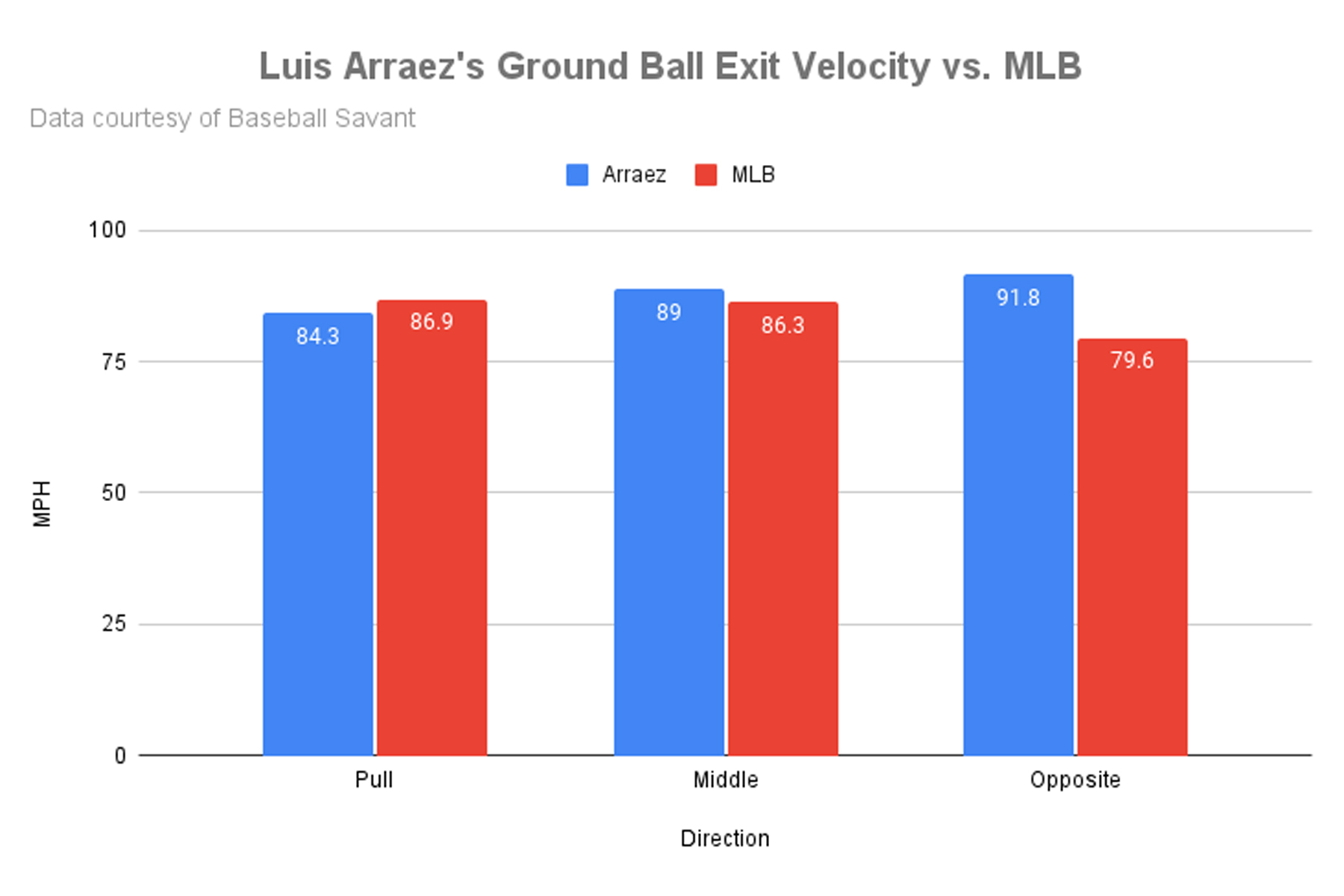

He actually doesn't do well (3-for-36) when he pulls the ball on the ground, which is still another unsurprising thing. He only hits those balls at an average of 84.3 mph, whereas ground balls to the pull side generally average 86.9 mph.

Yet when Arraez hits ground balls up the middle or to the left side of the field, he typically mashes them:

This is why Arraez is batting .426 on ground balls up the middle and to the opposite field, whereas the average hitter is batting only .288 when he tries that.

It's also why opposing teams don't bother shifting their infields against him. It's happened on only 3.0 percent of all pitches against him, which isn't close to the standard 56.7 percent shift rate for left-handed batters this season.

Between this and Arraez's fondness for competitive at-bats, his basic lesson on hitting can be summed up this way: The best way to beat 'em is to not make it easy for 'em.

Oh, and Make Pitchers Work

Arraez's 2022 season would be impressive enough if his .361 average was all he had going for him. But as his .443 on-base percentage shows, he's not just hitting his way on.

Notably, he's taking ball four more frequently. His walk rate is 11.9 percent, which is a career high and a tick above Aaron Judge for 23rd among qualified hitters.

As much as anything, this aspect of Arraez's season defies common sense. Not just in the sense that less powerful hitters should theoretically see more strikes, but also in the sense that his zone discipline hasn't undergone any immediately noticeable changes. His swing rates both inside and outside the zone are roughly in line with his career rates.

Yet one thing that has changed in Arraez's approach is his willingness to let the pitcher set the tone. Even more so than in previous seasons, he's not swinging at the first pitch:

- 2019: 18.8 percent

- 2020: 19.8 percent

- 2021: 20.8 percent

- 2022: 15.3 percent

To the extent that he's finding himself in 1-0 counts more often, this is working. It's also key that Arraez isn't toning down his discipline once he is ahead in the count. Quite the contrary, in fact. When ahead in the count between 2019 and 2021, he chased 25.6 percent of the pitches he saw outside the zone. This year? Just 20.8 percent.

That's a good way to get to ball four, and Arraez also has a method for extending at-bats. He's fouling off 47.1 percent of the pitches he swings at in the "shadow" of the zone when he's behind in the count. It's just 38.3 percent for the average hitter, which is to say Arraez is on another level when it comes to defending the strike zone.

Of course, the problem with the suggestion that other hitters might be like Arraez is that he didn't choose to be the hitter he is. This is the hitter he's always been. Even before he arrived in the majors, Baseball America's scouting reports raved about him as a "hit-tool fiend" with "hand-eye coordination [that's] off the charts."

Arraez's example is nonetheless more than worthy of appreciation, and not just because he's so many different kinds of good at what he does. He's living proof that, in order to be great, a hitter doesn't necessarily have to be better at doing what everyone else is doing.

Instead, he can be the best at doing his own thing.

Stats courtesy of Baseball Reference, FanGraphs and Baseball Savant.